Translator& Author's Notes

Welcome, Reader, a chara!

Thank you for taking the time to read Merlin - As Béal an Dragain and for visiting this page in order to learn more about the story itself.

Contents

Feel free to jump ahead!

Notes by chapter:

Getting Started

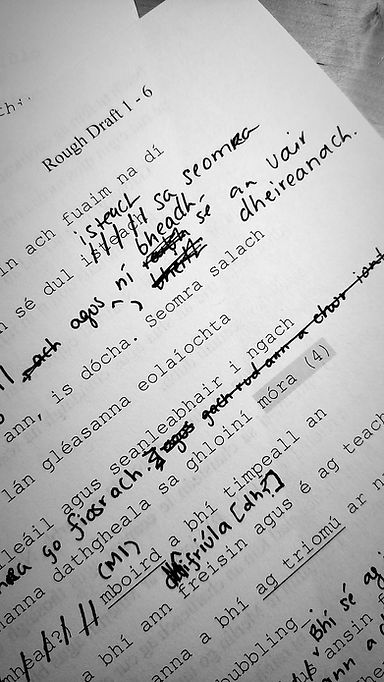

The project consisted of three main writing / translation tasks:

-

Translating the original English dialogue into Irish

-

Writing what I saw in detail in Irish scene by scene, with later embellishments to develop the narration more fully, and

-

Translating the Irish text and dialogue back into English.

*Phases 1 and 2 took place more or less simultaneously. Moreover, my Irish studies were supported by routine grammar exercises and 2-3 hours per week of speaking practice with trained teachers during the first leg of the project (end of May 2020 - August 2020). It was during this period that most of the first and second chapters were written.

At each stage of the writing and translation process, I attempted to keep detailed notes on the the difficulties I was met with, the practical and/or stylistic choices I made and the feedback I received from my teachers. By presenting these notes here, I hope to clarify a few points about various elements contained within the text while also providing you with an accurate understanding of the challenges A2-level students might face when creative writing.

General Notes on the Story and Dialogue Translation

If you have stumbled upon or followed a direct link to this story, there is a strong likelihood that:

-

You are an Irish speaker or learner, and quite possibly we have either met in the Gaeltacht or attended the same Coláiste,

-

You are a Merlin fan who may or may not speak Irish, but still likes a good Merlin-related tale, or

-

You and I know each other from the online language learning community.

As an Irish speaker, you may wonder why the English translation doesn’t always match up with the Irish original. There are three main reasons for this. First and foremost, there is a significant gap in my ability to express myself in both languages, mainly due to my limited vocabulary and grammar in Irish. Moreover, I strove to use the new words and expressions I had either recently learnt in my Irish lessons or purposefully looked up. My goal: to use these words and expressions at a high frequency in order to commit them to memory and improve my accuracy with a limited word pool. That said, I opted for synonymous expressions in the English translation in order to avoid repetition and more fully develop the narrator’s voice, while trying to capture the humour of the original Irish. Finally, my aim of presenting the story in a readable digital form meant that I would need to consider line length and sentence structure, which led to late-stage paraphrasing or altered sentence structure to fit the allotted space for each line or paragraph.

As an Irish learner, you might be hesitant to use this story as a resource without knowing how accurate the text is. Here I should note that the text is not mistake free, but is rather meant to serve as an example of creative writing and translation at the A2 level. For this reason, A1 and A2 level concepts were given precedence and wordy or intermediate/advanced constructions only seldomly appear. More advanced students may notice the following:

-

A higher degree of accuracy in usage of: the simple past tense, common verbs which require prepositions, application of séimhú, urú or tada following prepositions, and case and number changes to high frequency words in context.

-

A certain degree of error regarding: adjective declension and the structuring of complex sentences (i.e. clásail dhíreacha and clásail neamhdhíreacha).

-

An occasional degree of clunkiness or error in: phrasing or word choice. Double genitives may appear in this regard.

On the whole, later chapters were simultaneously quicker to write and demonstrate calculated grammatical risks (i.e. attempts to use more complex structures than appear in the first two chapters, because I was introduced to them much later in the writing process).

So, what has been corrected and/or edited by a professional Irish teacher?

My full Irish translation of the original English dialogue was reviewed and corrected by my teacher Mollie. She had not seen the series herself, but we read through the dialogue together in an attempt to root out my mistakes and make the dialogue sound more natural. Changes to the dialogue at this stage were relatively minor, apart from some trickier lines which required sentence restructuring.

Additionally, the first three scenes of Chapter 1, i.e. Tosaíonn ár scéal le sliocht ón Dragan Mór, Téann Merlin go Camelot, and An bású were edited in full by my teacher Ryan, who had also not seen the series at the time. After discussing his feedback on these sections, he answered my remaining questions and provided examples to explain my mistakes. I took most of his edits readily, although there were a handful instances where my original line was maintained after briefly clarifying the grammar/usage. I then proceeded to treat this edited portion of Chapter 1 as a reference when questions about grammar arose in later stages which went unchecked by my teachers.

As fellow language learners and polyglots in the online community, you may ask yourselves whether this type of writing exercise will have an impact in your general skills in your target language at your current level. From my own experience, I believe it would. Here are some of the improvements in my skills which I’ve noticed since I first began the project in May 2020:

-

The repetition required to write a text of this length has allowed me to stockpile common phrases used in the story and improved my accuracy on the grammatical topics I specifically learned to apply to the text.

-

My reading skills improved significantly, which allowed me to focus more on unknown vocabulary than understanding the flow of the texts we covered in my A2 level online courses this year.

-

I recently realised, as I took a break to watch a handful of other episodes of Merlin, that I am now able to spontaneously interpret the dialogue and narrate episodes without consulting a dictionary. This is not to say that these interpretations are entirely fault free, although this is a skill which I use in other languages which I had not been able to use to practise my Irish before now.

Caibidil 1 - Fáilte go Camelot

Tosaíonn ár scéal le sliocht ón Dragan Mór

Despite appearing as the first line of spoken text in "Merlin - The Dragon’s Call", this was the last line of dialogue to be completed due to the complexity of the original sentence structure. I initially changed ‘No young man … can know his destiny’ to ‘Níl a fhios againn cén chinniúint go bhfuil againnse féin,’ (lit: We cannot know what fate has in store for us) as a simplification, but decided to keep this use of ‘we’ throughout the first half of the quote, thinking it would compliment the voice of the narrator, who goes on to comment on the nature of fate in later scenes.

I additionally split the sentence ‘And so it will be for the young warlock arriving at the gates of Camelot, a boy that will, in time, father a legend. His name: Merlin,’ to ‘Inseoidh mé an scéal céanna daoibh faoi mórdraoi óg a bheidh ag teacht ar na ngeataí Chamelot ar ball beag. Is é an t-ainm atá air Merlin agus buachaill a bhunóidh seanchas atá ann’ (lit: I will tell you a similar story about a young warlock who will be arriving shortly at the gates of Camelot. His name is Merlin and he is a boy who will father a legend) because earlier versions read as though two distinct people, i.e. a warlock and a young boy, were arriving at Camelot’s main gate rather than one: the young boy and warlock Merlin.

Téann Merlin go Camelot

This first scene has received the most attention in regards to time spent writing and editing, especially as it strictly adheres to the write-what-you-see-in-the-order-you-see-it method, while simultaneously attempting to set the scene. In later drafts, the background information related to Camelot as it is portrayed in the show was added.

Príomh-Gheata is capitalised and hyphenated similarly to how the same term appears in Nicholas Williams’s Irish translation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s “An Hobad”.

An bású

The lines spoken by Uther in this scene were heavily edited by my teacher. The lines of both Uther and the Great Dragon were often related to legal jargon and fate, respectively, and/or consisted of a complex web of grammatical clauses, the equivalent of which far surpasses my current understanding of Irish sentence structure. This is why the lines of these two characters tend to be noticeably simplified, yet close in meaning to the orignal in the series, compared to the lines of other characters which more easily lent themselves to direct translation.

I specifically translated ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth’ as ‘Ghlac tú mo chroí, m’áthas, is mo mhac uaim,’ (lit: You stole my heart, my happiness and my boy from me) more loosely, since the established Irish expression was unknown to me, and at the time and stage I was actively trying to avoid overly relying on the dictionary.

Rún Mherlin

In this section I ran into the concept of strong versus weak adjective declension in the genitive case, specifically with bright-coloured, i.e. dathgheala (strong plural) and dathgheal (weak plural).* Knowing that this topic was more advanced than my current level of studies called for and that studying it would take me down a rabbit hole, I decided to temporarily wait to cover this topic.

Hunith’s letter was also a high-level difficulty translation, mostly due to the use of conditionals, multi-clause sentences and modal verbs.

*My initial focus at the start of this project was to improve my use and knowledge of verbs (specifically type 1 verbs in the past tense). My knowledge and application of rules relating to noun classes and adjective declension is weak at present, although my ability to recognise patterns related to high-frequency nouns and adjectives in the story did improve markedly towards the end of the writing process.

Caint leis an rí

The Merlin series differentiates between two types of magic users: Druids (members of a distinct community/culture with powerful magic) and other magical and/or magic-wielding individuals. Merlin himself belongs to the latter category in the show, although his fate is closely entwined with the prophecies of the Druids.

I was unsure of how to make a clear distinction between these two groups using Irish vocabulary related to sorcerers. (In English, for example, I am wont to use terms such as enchantress, witch, hag, warlock, wizard, magician, etc. in different contexts. While I am aware of Irish terms such as draoi, draíodóir, asarlaí and geasadóir, I have not read enough material using these terms to judge their appropriateness as relates to this story.)

In the end I decided to use use drȳ-menn (m.nom.pl.), the Old English word for Druids, to refer to the Druids present in the Merlin series. Old English is the language used in spells in the Old Religion, which the Druids are known to practise throughout the series. Moreover, I am actively engaged in Old English studies, so it seemed like a suitable option for The Merlin Project.

Sa choill

Throughout the story I tried to write the details of what I saw as they appeared. This strategy caused some difficulty in this scene, as the scene shifts from what is happening inside the tent to outside the tent on several occasions. Rather than changing this order, I attempted to transition between the two locations, although the switch may seem abrupt.

I hope you're enjoying The Merlin Project. Don't forget to fuel up before you keep reading!